In Korea, the reason we enjoy warm guk (soup dishes) in winter is to warm our bodies in the cold climate, replenish nutrients, and find psychological comfort through warm food. There are dozens of representative Korean winter soups, but still, at home we make soups using ingredients that are easily available. Also, in the old days, traditional ondol culture and food culture intertwined, so soup culture has continuously developed and continues to this day.

Emotionally, Koreans maintain and preserve body temperature through winter soup dishes. On cold days, warm broth makes you warm inside, raising your body temperature and giving psychological stability. Through soup dishes, we get nutrition and a sense of fullness. In winter, there’s a food culture of wanting to fill your stomach solidly with warm food, ease the emptiness, and gain energy. For most adults, there’s a soup dish that their mother preferred making at home.

Korean homes have ondol heating culture. Korea’s traditional ondol culture developed a cooking method using heat from the fire pit, which made soup dishes commonplace in daily life.

In traditional meaning, eating tteokguk on New Year’s Day and other holidays to wish for longevity and good fortune is one reason, including the tradition of eating seasonal winter foods. Major winter soup dishes include tteokguk, gomtang, galbitang, kimchi-guk, and ugeoji-guk. We spend winter healthily by drinking warm broth and sweating.

Why Korean Soup Dishes Are So Diverse

In Korean cuisine, soup dishes occupy an important position, and their types and flavors are very diverse. This diversity has been formed by Korea’s history, geographical characteristics, abundance of ingredients, and cultural factors. Now let’s look in detail at why Korean soup dishes are so diverse.

Historical Background

Like food in all countries, Korean soup dishes have a long historical background. Korea was an agricultural-centered society, and we made soup dishes using various ingredients obtained while farming. For example, doenjang-guk and kimchi-jjigae are representative soup dishes utilizing fermented foods. These traditions have been passed down through generations, becoming more diverse and developed. Even in high-class cuisine like Joseon Dynasty royal court cooking, various soup dishes developed. In the palace, they made deeply flavorful soup dishes using various ingredients and cooking methods, and these dishes gradually spread to ordinary households.

Geographical Characteristics

Korea has a climate with four distinct seasons, and various ingredients are produced for each season. In spring, fresh ingredients like mountain vegetables; in summer, seafood; in autumn, harvested agricultural products; in winter, stored fermented foods – these are used to create various seasonal soup dishes. For example, in winter, gomtang and seolleongtang are popular for warming the body, while in summer, cold naengmyeon broth is beloved.

Abundance of Ingredients

Korean soup dishes use distinctive ingredients by region. In coastal areas, seafood soups like maeuntang and haemultang developed using fresh seafood, while in inland areas, dishes like doenjang-guk and gamjatang developed using ingredients from mountains and fields. This abundance of ingredients makes soup dish diversity even richer.

Cultural Factors

In Korean food culture, families gathering together for meals is valued as important. Soup dishes are an element that cannot be missing from these family meals, as they’re suitable for many people to share together. Also, in traditional Korean table settings, soup dishes are basically provided with rice, and this is one reason soup dishes occupy an important position in Korean dietary life. Also, Koreans value health, and soup dishes are a way to consume various healthy ingredients all at once. For example, samgyetang is boiled together with chicken, ginseng, and jujubes, making it highly nutritious and popular as health food.

Modern Changes

Unfortunately, in modern times, various ingredients are cultivated regardless of season, and with diverse foods imported from abroad, soup is being somewhat neglected. Also, various cooking methods from foreign countries are influencing Korean soup dishes. For example, foreign soup dishes like Japanese ramen or Chinese hotpot have been transformed Korean-style and are establishing themselves as new soup dishes. These changes are further broadening the diversity of Korean soup dishes.

When You Visit Korea in Winter, What Soup Dishes Do I Recommend?

You can expect costs of around $10-20 per person. For Korean restaurants specializing in soup dishes, I recommend galbitang, samgyetang, and mandu-guk.

Once I was eating at a samgyetang restaurant and saw a traveling couple order samgyetang. They made an amazed expression when they saw the samgyetang come out – a whole chicken boiled thoroughly white. Of course, when you eat samgyetang, kimchi and kkakdugi are provided as basic side dishes. Basic side dishes are free. Chili peppers and doenjang are also provided. The main ingredient of samgyetang is young chicken. (No sugar is used.) When eating samgyetang, dip the meat in salt, or add or reduce salt according to your taste. Add a little pepper too. For reference, it’s not a spicy dish.

I also recommend mandu-guk in winter. A dish similar to mandu is Chinese dim sum. The difference is that mandu-guk boils mandu submerged in water. At this time, the water used for boiling also uses broth for flavor. Ingredients for making mandu include minced beef, pork, various vegetables, and seasonings shaped into dumplings. It’s not a spicy dish. No sugar is used.

There’s galbitang, and there are many restaurants that specialize only in galbitang. Galbitang is mainly made by cutting and boiling the beef rib part and the meat attached to the ribs. At this time, to make the broth delicious, each specialized restaurant mixes herbs and various ingredients. It’s mainly eaten in winter. No additional sugar or red pepper powder is used during cooking. In other words, it’s not a spicy dish. After eating a bowl in cold winter, warm energy fills your whole body. Prices are mostly around $10-20.

This one has mixed preferences, but ppyeodagwi haejangguk might be a bit difficult for first-time visitors to Korea. Pork spine is boiled for a long time to remove the smell, then boiled with various vegetables and medicinal ingredients. The taste is spicy, and no sugar is used when making ppyeodagwi haejangguk. When you order ppyeodagwi haejangguk, you eat the bones, meat attached to the bones, and vegetables together. Side dishes come separately too. Of course, side dishes basically include kimchi and kkakdugi. The reason Koreans prefer it is that eating ppyeodagwi haejangguk makes you sweat a little all over your body, and with the added spiciness, your mind can reset momentarily. Many people say that after eating, stress is completely relieved.

If you want to eat kongnamul-gukbap, I recommend trying ‘kongnamul-gukbap’ after visiting Korea. It costs around $10 at most. The reason people prefer kongnamul-gukbap is for winter warmth, and because kongnamul-guk contains a lot of asparagine acid which is very good for hangover relief. Bean sprouts themselves contain a lot of asparagine acid.

Bugeoguk is also commonly eaten. It’s food made by thoroughly boiling dried pollack. There aren’t that many bugeoguk specialty restaurants, but if you’re interested in bugeoguk made with dried pollack, I recommend it once.

Chueotang is soup made with loaches, and anyway this might have mixed preferences. Chueotang is rich in protein and preferred as very good food for men. Of course, it’s also eaten for health. Chueotang is a slightly spicy dish. My mother used to make it a lot in the past. The cooking method for chueotang in restaurants: loaches (similar to eels but much smaller in size. The size of loaches is about adult palm length) are thoroughly boiled, then strained through a sieve to filter out only the flesh. Then doenjang, gochujang, salt, and seasonings are added and thoroughly boiled – that’s loach soup. Personally, I eat chueotang about 5 times a month, and after eating, my stomach feels comfortable. The price is around $10-15, and all side dishes come out. Some people say chueotang is fishy, but it’s not particularly fishy. However, it is a slightly spicy dish. After eating, I think your stomach will feel full and satisfied.

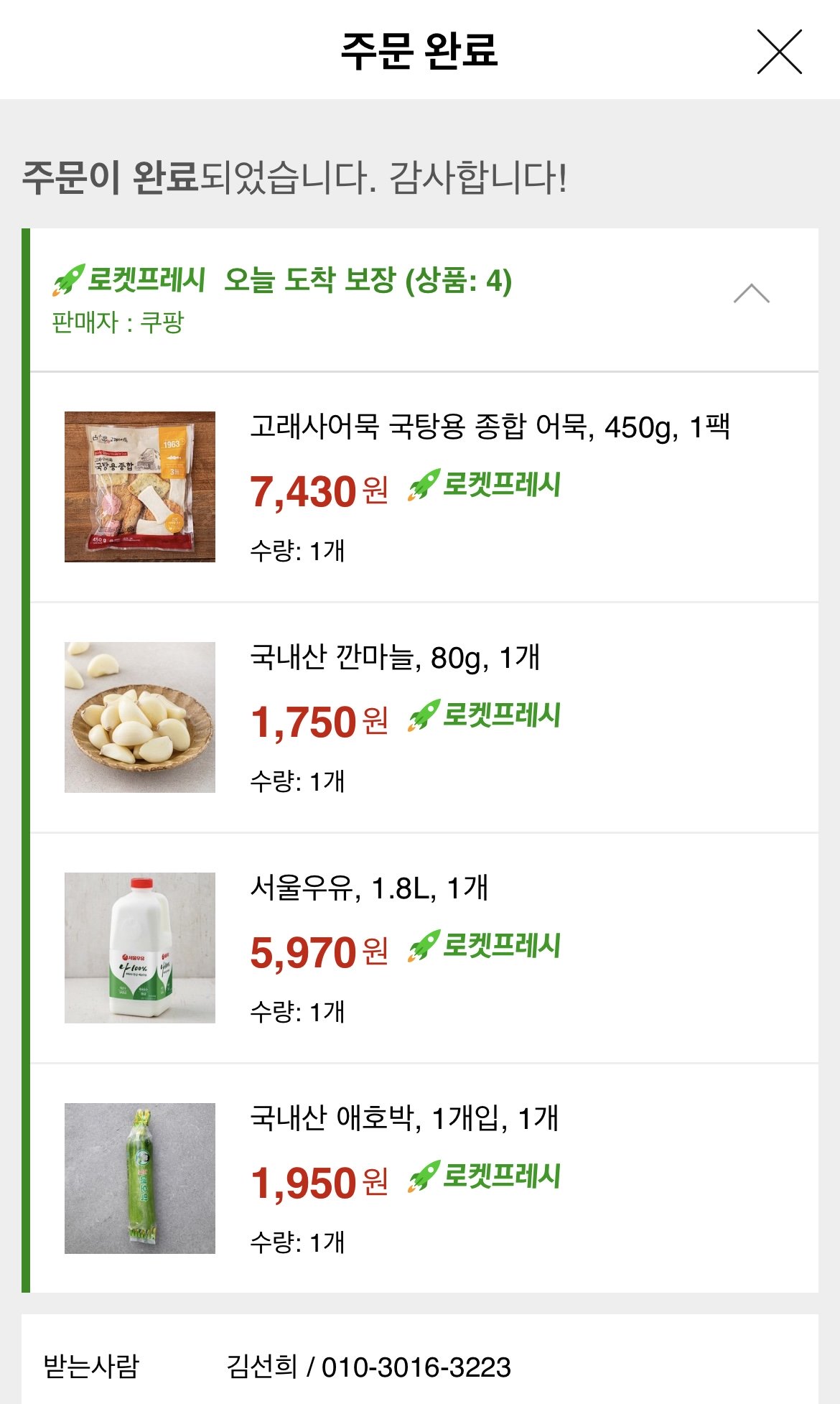

Also, soups commonly made at home in winter include beef radish soup (beef and radish boiled thoroughly), kongnamul-guk, kimchi-guk, radish soup, and mandu-guk. Simply put, you can think of Korean guk as boiling various ingredients in water to bring out the unique flavor of the ingredients. For reference, the difference between jjigae and guk is that jjigae has richer taste and slightly stronger seasoning than guk. Guk has clearer broth than jjigae and slightly milder seasoning.

If you don’t prefer spicy things, I recommend samgyetang or mandu-guk. If you choose samgyeopsal or beef short ribs as your menu, one of kongnamul-guk, doenjang-guk, miyeok-guk, or oi-naengguk (cold cucumber soup) will come out as a side dish with the menu, so you can try that.

For reference, in Korea, for beef short ribs, based on 1 serving (140g-200g), if it’s Korean hanwoo raised in Korea, you can expect a price of around $40-60. Honestly, if you’re considering beef short ribs as a menu with your family during Korea tourism, I’d recommend it even though the price is a bit expensive. Because you can feel various side dishes all at once. Above all, side dishes are free and continuously refilled.

Really brand-name beef short rib specialty restaurants in Seoul are around $60 per person. The meat served differs by restaurant, but it’s likely one portion of 150g-200g. Honestly, the day you eat Korean hanwoo beef short ribs at a restaurant in Korea should be at least a birthday. Or when the company pays during a work dinner…

If you eat food somewhere other than Seoul, I strongly recommend it. Seoul is 10% to as much as 30% more expensive for food than provincial areas. Due to expensive rent and labor costs.

One interesting fact is that if you eat at restaurants outside Seoul, depending on the restaurant, you’ll feel that side dishes and food taste are distinctive.

This winter soup tradition connects closely to Why Soup Is Served in Most Korean Meals

Many winter soups rely on fermentation explained in Why Korean Food Uses Fermentation

To understand rice and soup together, see How a Korean Meal Is Structured

Everyday home soups are part of What Is Mitbanchan?