why soup is served in korean meals

In Korea, soup is called guk

Traditionally, the basic menu for setting a Korean table has centered around rice and soup. And then we prepare the day’s side dishes or a main dish. At the very least, during mealtime in Korea, there must be either soup or stew—one of the two. And to this, we add kimchi and various other side dishes. In other words, without broth on a Korean table, it feels quite empty. That’s why from my mother’s time, whenever preparing a family meal, she always made soup.

Soup was considered so important that this saying even emerged and is still used: “There’s not even broth left.” In Korean, when we say there’s not even broth left, it means there’s nothing at all. It means I won’t extend any more goodwill to the other person, and there’s nothing left for me. As a result, it means I won’t maintain the relationship anymore—in short, it signifies a complete break with you.

This shows how we can glimpse the status of soup even in our language habits. Even in modern society, Koreans always prepared soup for meals. In my father’s time, and in my time as I became a father, Korean tables always have soup. The elderly used to say, “Without soup, you can’t eat rice.”

Korean cuisine has particularly well-developed soup culture, and there are many varieties. We make soups using seasonal ingredients, and there are several soups we specially prepare for holidays or special occasions. On birthdays we eat seaweed soup, on New Year’s we eat rice cake soup, and on Chuseok we eat taro soup. Also, after drinking with friends, we eat hangover soups like bean sprout soup, dried pollack soup, haejangguk, or sundae soup to detoxify our alcohol-laden bodies. If you add all the regular soups we normally eat, the varieties of soup are incredibly diverse.

According to my nephew who lives alone in Seoul while working, he used to mainly eat out before, but now he says restaurant food doesn’t taste good, so he cooks soup and rice himself at home.

It’s said that in the 18th-19th century, the Korean king alone ate 64 different types of soup. So you can see how developed soup culture was in Korea.

Is soup culture really a unique characteristic of Korean food?

It’s clear that we love brothy foods including soups. And it’s also undeniable that Korean cuisine has many brothy foods including soups and stews. But does that mean we can say soup culture is a unique characteristic of Korean food? I don’t think so.

Because various forms of soups and similar foods exist worldwide. Even in Western cuisine alone, there are various soup dishes and brothy foods. What immediately comes to mind is the soup that Europeans enjoy eating. European soups come in many varieties—there’s thick soup, stew with meat and vegetables, porridge, and broth. There’s clear consommé, thick chowder, and purée made by boiling and mashing vegetables.

Chinese and Japanese cuisine are similar. Boiling and steaming cooking methods are used as basic recipes not only in Korea but throughout Asian cooking. Chinese and Japanese people also eat many types of tang, like our soup. In Asia, the form of boiling food in water and adding various ingredients is similar.

Why soup culture is somewhat unique as a characteristic of Korean food?

In Korean history, there’s a term called “il-sik sam-chan” (一食三饌). This means preparing one bowl of white rice with three side dishes for a meal. Soup is not included in this count. Soup is basically assumed to be part of il-sik sam-chan. For example, if I prepare dinner for my child today, I’d make rice, bean sprout soup, braised anchovies, braised beans, and seasoned vegetables, and for the remaining one dish I might add stir-fried spicy pork. In other words, in Korea, soup is included with rice. Rice and soup are not separated in a meal but integrated as one.

When you go to a restaurant while traveling in Korea, the basic table setting places soup to the right of the rice. This is because it’s cultural. An easy way to understand it is to think of soup as food with liquid that’s generally made by boiling in water.

While the West and Japan think of soup as separate, Korean rice and soup should be seen as a fused relationship that becomes one.

Another reason Koreans prefer soup is not actually because we can’t eat rice without soup, but because rice and soup give such a sense of unity in a meal. We don’t find the characteristics of Korean food culture in soup simply because Koreans like brothy foods or because there are many types of brothy foods.

For example, when eating samgyeopsal or spicy food, we serve mildly seasoned soups like bean sprout soup or seaweed soup alongside to soothe the spiciness from the food.

When did soup culture develop?

Historically, it appears our people (Korea) have enjoyed various soup dishes since ancient times. In terms of linguistic interpretation, what we call “guk” in Korean—food made by putting various ingredients in water or other liquids and boiling them—was expressed in Chinese characters as “tang” (湯). But in very ancient times, they distinguished more precisely and the names were really different. This story goes back to around the 1300s.

Since these were ancient foods that existed before Hangul was created, we don’t know what they were called in pure Korean, but they remain in Chinese characters.

Looking at documents from the Goryeo and Joseon periods in Korean history, it seems our ancestors really loved soup. The 18th-century Joseon scholar Seongho Yi Ik left this writing: “Bibimbap never gets boring no matter how much you eat it, but for filling your stomach, gukbap (soup with rice) is the best.” Historically, the Korean people were famous for enjoying bibimbap, but they equally enjoyed gukbap—that is, soup and rice. Back then, food wasn’t as abundant as it is now.

Why did soup culture develop?

Looking at Korea, Asia, and various countries, unique food cultures have taken root. The formation of these food cultures is influenced by various factors. Particularly, the country’s historical, economic, geographical, and climatic characteristics must have intertwined comprehensively to create a unique soup culture.

As with any country, soup basically emerged as a way to eat food deliciously. In other words, in the process of food development, foods like soup and stew emerged either independently or dependently with other dishes.

Another reason is to eat more rice. This may sound strange to modern people, but from an old perspective, the characteristics of Korean food are contained in soup culture. Some argue that soup is a product of poverty. They claim that because the Korean peninsula has many mountains and narrow terrain, grains weren’t abundant, so soup developed in the process of adding water to limited ingredients and boiling them to increase the quantity.

However, historically, Korea was not a chronically food-scarce poor country. Also, soup actually promoted grain consumption. Unless it’s a separate dish like Western soup, having soup makes you eat more rice. In that sense, soup was a food of abundance and an upper-class dining culture. So the biggest reason soup culture developed in Korea can perhaps be found in rice, our staple food.

Korean food culture developed centered on rice. In the West, it developed centered on bread. We eat kimchi as a basic side dish along with meat and various side dishes, all centered on rice and soup. Most side dishes also seem like supplementary foods to help us eat delicious rice-cooked meals in larger quantities. Also, borrowing my wife’s words about meals, side dishes play various roles in supplementing missing nutrients. These side dishes are also prepared differently according to the seasons.

From a regional perspective, Korea’s ondol culture of always boiling water in cauldrons, along with climatic and environmental factors—cold and dry winters, hot and humid summers—probably also played a role. By eating hot broth, we warm our bodies, and even in summer, we can feel coolness by sweating sufficiently, so soup is consumed as an efficient food to endure the sweltering heat.

Korean soup culture was formed not simply at the level of eating delicious food, but by Korean life and natural conditions all melting and mixing together. The reason soup emerged wasn’t just one reason but varied according to history, natural environment, and culture. Even now in Korea, soup is the most basic food that comes to the table.

What do we mainly eat this winter?

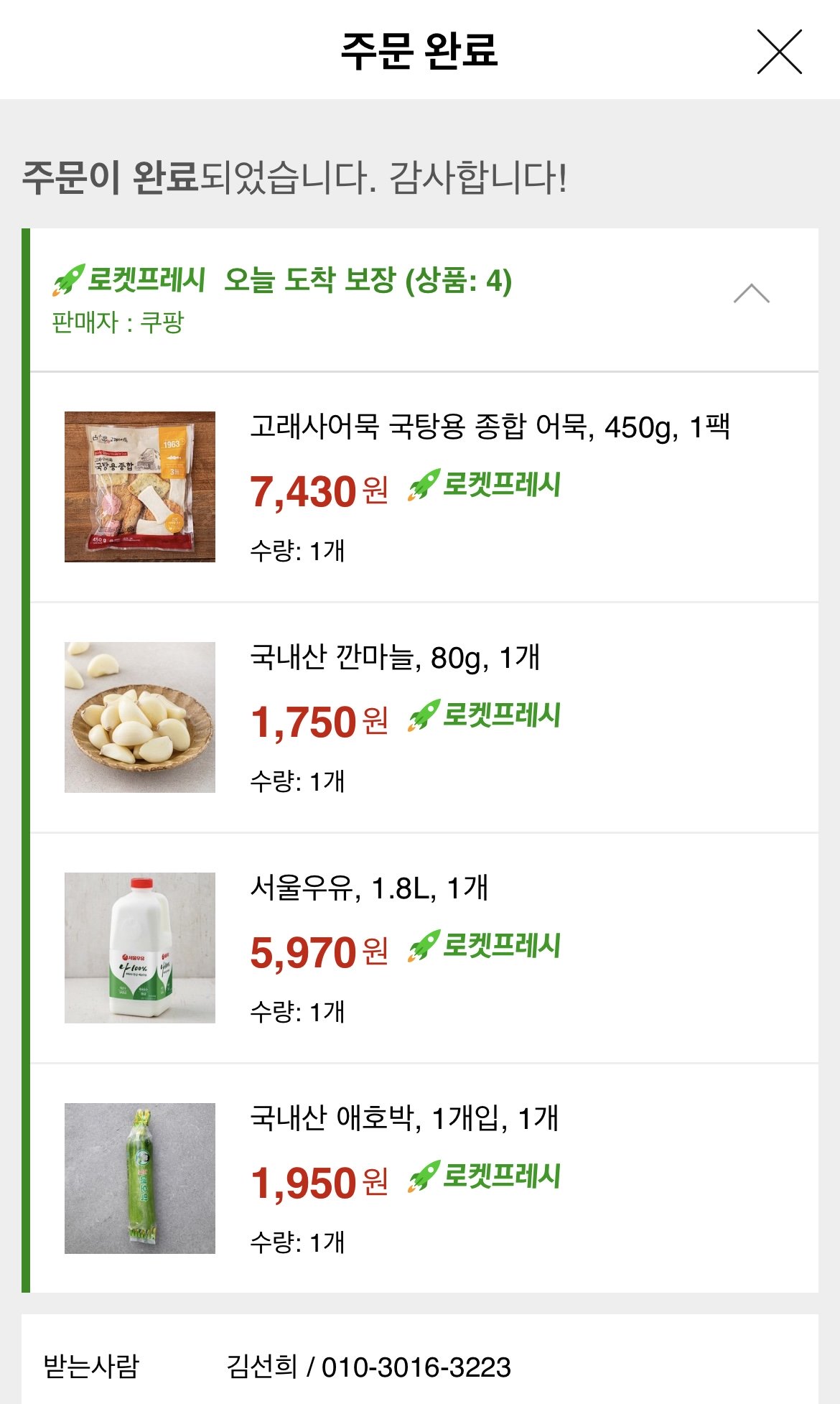

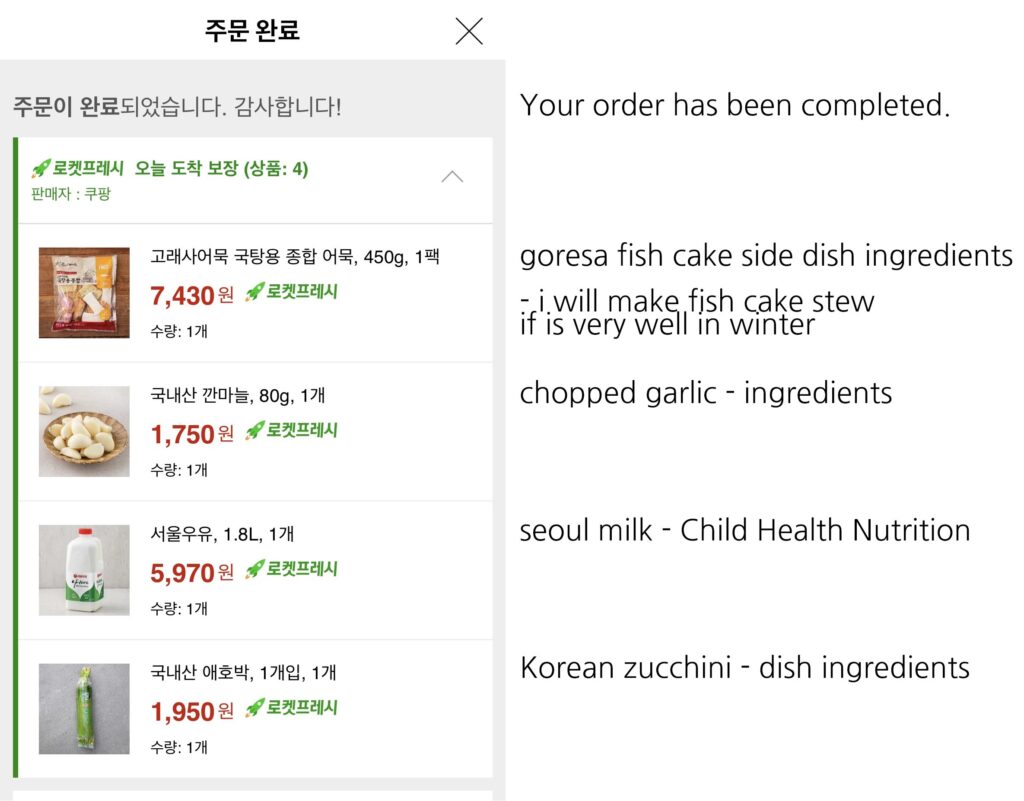

In cold winter, we mainly prepare soups that warm the body. The methods also differ from household to household. We try not to use sugar in these as much as possible.

In cold winter, there are various options: bean sprout soup (soup made by boiling bean sprouts with a bit of salt), seaweed soup (soup made by stir-frying seaweed in sesame oil, adding various seasonings, and boiling thoroughly), soybean paste soup, kimchi soup, beef soup, radish soup, and more. The soup I prefer is definitely radish soup, which I learned from my mother-in-law and make often. The preparation time is short, and when you eat it, you feel warmth in your chest and stomach. Because it doesn’t have many ingredients, the taste is also clean. No sugar is used

Today Lunch is pollack soup, Sugar free

Korea traditionnal hangover soup , Pollack Soup, We call Buk-eo Guk

This is the classic hangover soup I had for lunch today: pollack soup(. I added a bowl of rice, and the three side dishes are as follows: seasoned red pepper paste, seasoned bean sprouts, and cubed radish kimchi (radish kimchi) from the left, clockwise. It costs about $9.

To understand how rice and soup function together, see What Is Korean Food, what is mitbanchan