Korean eating culture reflects how food shapes daily life, emotional comfort, and social relationships in Korea.

Why Eating Is So Important in Korea

In Korea, eating is not just a daily routine—it is something people genuinely care about.

The question “What should we eat today?” often marks the real start of the day, and it carries more weight than it might in many other cultures.

Because eating matters so much, competition in the food industry is intense. Restaurants constantly work to satisfy demanding customers, and as a result, better and more creative menus continue to appear. New “hot places” are born every day. If I had to name one reason Korean food tastes so good, it would be simple: supply and demand.

But this raises another question. Why are so many Koreans—including myself—so deeply focused on food?

Like most parents in the world, parents are always concerned about whether their children are eating well.

Today’s menu, from top left, is pumpkin soybean paste stew, rice, spicy pepper jangajji (pickled spicy peppers in soy sauce), pumpkin pancake, dad’s rice, and dad’s soybean paste stew. Today, I made it myself, with my beloved son 😉

Food and Stress in Korean Eating Culture

One possible answer is stress.

It often feels like many people in Korean society use food as a way to relieve stress, which has become a defining part of Korean eating culture. There are two ways to look at this.

First, Korea is a high-stress society overall.

Second, there are not many easy ways to release that stress.

When stress is everywhere and options for relief are limited, eating becomes the fastest and most accessible solution. Of course, this is just my personal hypothesis—but it feels convincing.

Korean Office Lunch Culture and Daily Eating Habits

This pattern is especially visible in office life. Like workers around the world, most Korean office workers eat lunch out with colleagues. Seasonal preferences strongly influence these meals. In summer, people crave cold noodles. In winter, warm soups are everywhere. Younger generations lean toward foods like tteokbokki or pork cutlets—choices that reflect their era.

In Yeouido, Seoul, where I work, I often go to a small baekban restaurant. It’s not especially cheap, but not expensive either. A typical meal costs around nine US dollars. You get a warm bowl of rice, soup, and several side dishes—simple, balanced, and comforting.

When Food Becomes the Only Escape

There is no doubt that eating delicious food brings joy. It is one of life’s great pleasures, and it is certainly one of mine. However, when food becomes the main tool for stress relief, problems begin to appear.

Weight gain, lower self-esteem, guilt—and eventually, even more stress. This cycle is surprisingly hard to break.

How Modern Korean Eating Culture Has Changed

One big difference between my childhood and today is convenience. Now, chicken or pizza can be delivered within 30 minutes, almost anywhere. Another major change is the rise of ultra-processed foods.

When I was younger, flour-based foods mostly meant noodles. Today, pizza and hamburgers are everywhere. They are still not considered traditional staples in Korea, but younger generations eat them far more often than we ever did.

Finding Comfort Beyond Food in Korean Daily Life

That’s why it’s important to find ways to comfort ourselves that don’t involve food. Something as simple as walking can help release stress while clearing the mind. Food should remain a source of pure enjoyment—not a coping mechanism. After all, we eat every single day.

A Parent’s Everyday Reality

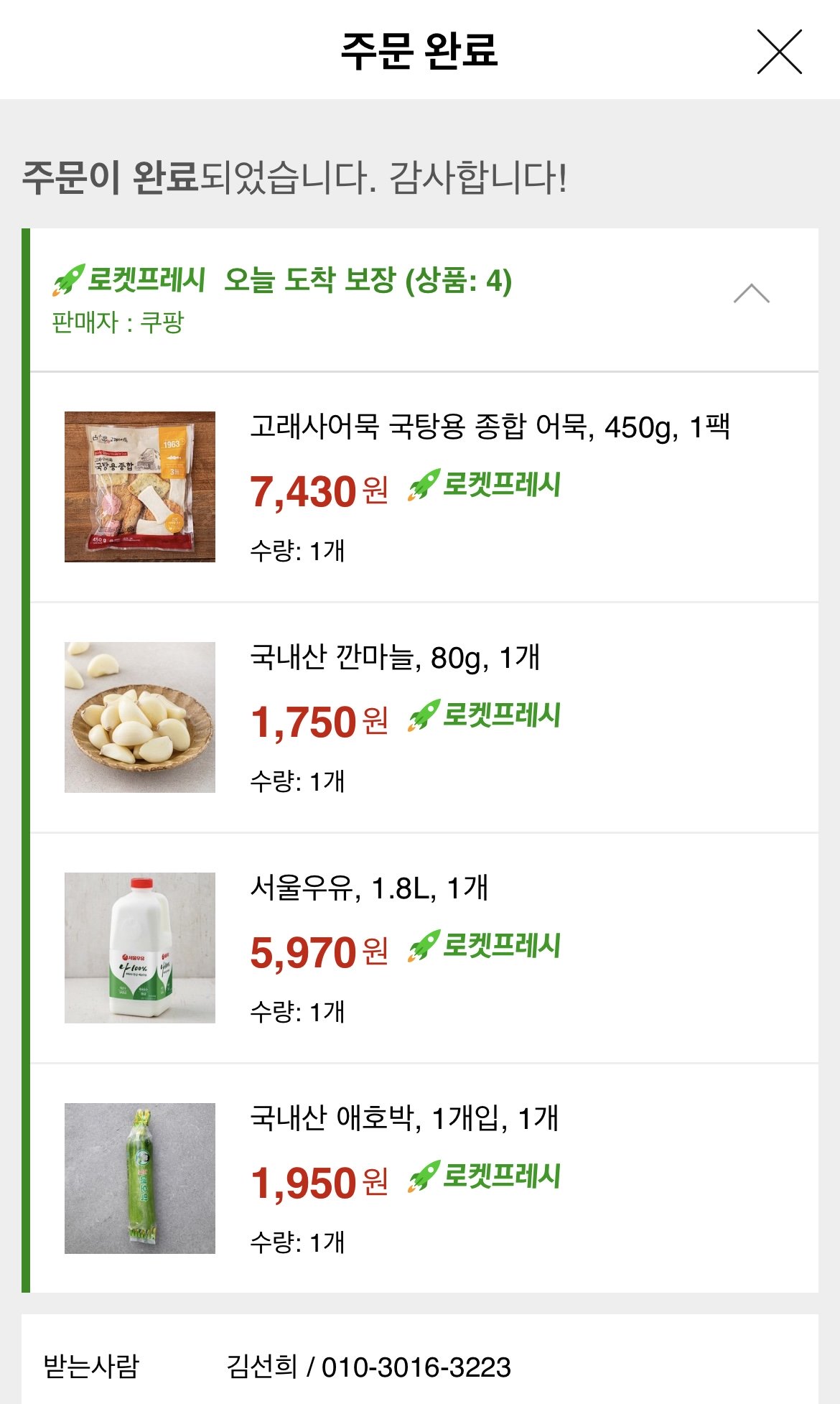

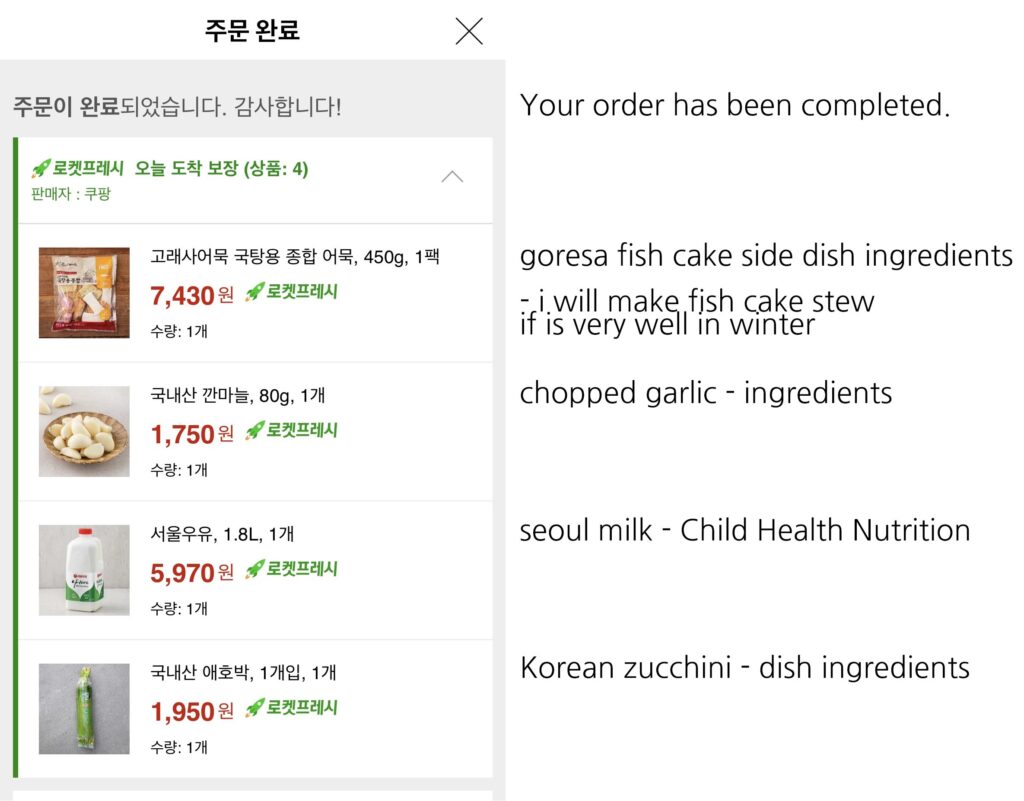

After work, I often come home, look at what little food we have left, and ask my child,

“Hey—what do you want to eat tonight?”

I give him a few options and let him choose. On days when there’s almost nothing in the fridge, dinner becomes fried rice with eggs, kimchi fried rice, or soybean sprout soup with a fried egg and a few side dishes.

In the end, parents everywhere are busy taking care of their children’s meals—and their own.

And yes… I really hope this blog does well.

This is why Korean eating culture continues to shape everyday life in Korea, beyond food itself.

you may be more insteresting my article

- Korean Banchan: How Seasons Shape the Korean Table

- Why Korean Tables Are Filled with Side Dishes

- What Is Korean Food?

- You may be interested in korea banchan – google image search result