Introduction

Korean dining tables always feature certain beloved menu items. Throughout spring, summer, fall, and winter, Koreans prepare guk (soup), tang (rich broth), jjigae (stew), and jeongol (hot pot) using seasonal ingredients appropriate for each time of year.

What is Guk (국)?

The dictionary definition of ‘guk’ is a dish made by adding a large amount of water to meat, fish, or vegetables and boiling them. If we had to specify the ratio of water to ingredients, it would be roughly 6:4 or 7:3.

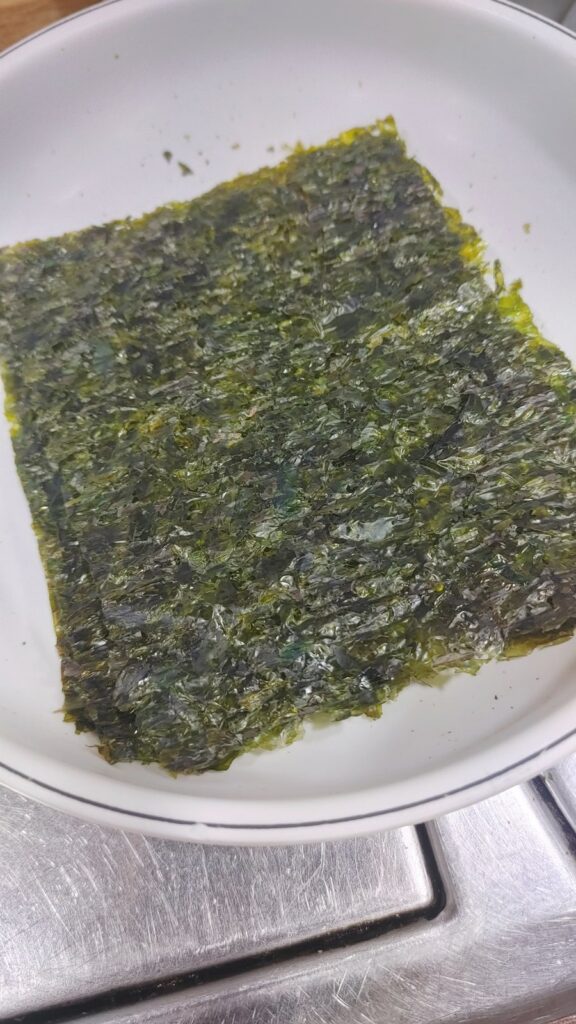

Guk is frequently prepared for every meal, and its cooking time is much shorter compared to jjigae or tang. In my home, at baekban (Korean set meal) restaurants, and during Korean office lunch hours, various types of guk are prepared at each establishment: egg soup (gyeran-guk), dried pollack soup (bugeo-guk), seaweed soup (miyeok-guk), bean sprout soup (kongnamul-guk), beef radish soup (sogogimu-guk), dried napa cabbage soup (ugeoji-guk, which uses dried vegetables and adds doenjang for seasoning), soybean paste soup (doenjang-guk), and radish soup (mu-guk, which I frequently eat during cold winters).

Another important thing to know is that the ingredients for these soups are somewhat less expensive compared to tang or jjigae, and they’re made using seasonal vegetables. For bugeo-guk and miyeok-guk, dried seaweed and dried pollack (called bugeo) have excellent storage qualities. Compared to other jjigae or tang dishes, the ingredient preparation and handling are simpler, making them more convenient to prepare and eat at home.

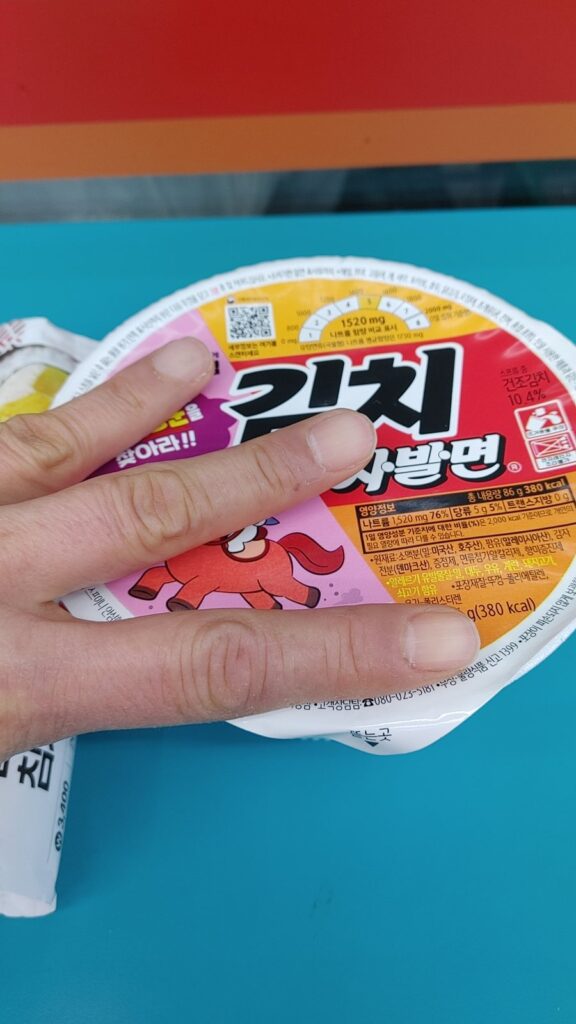

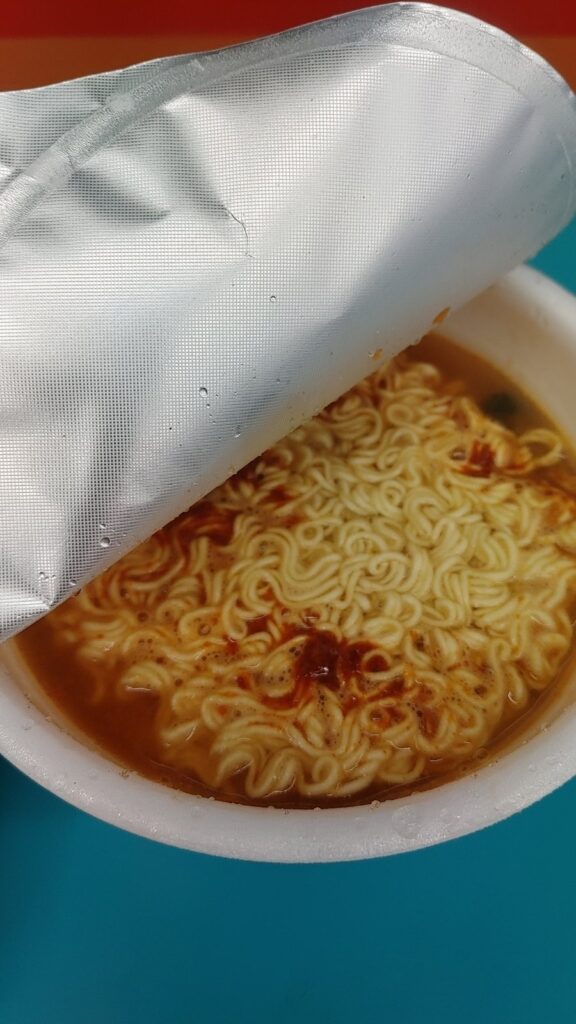

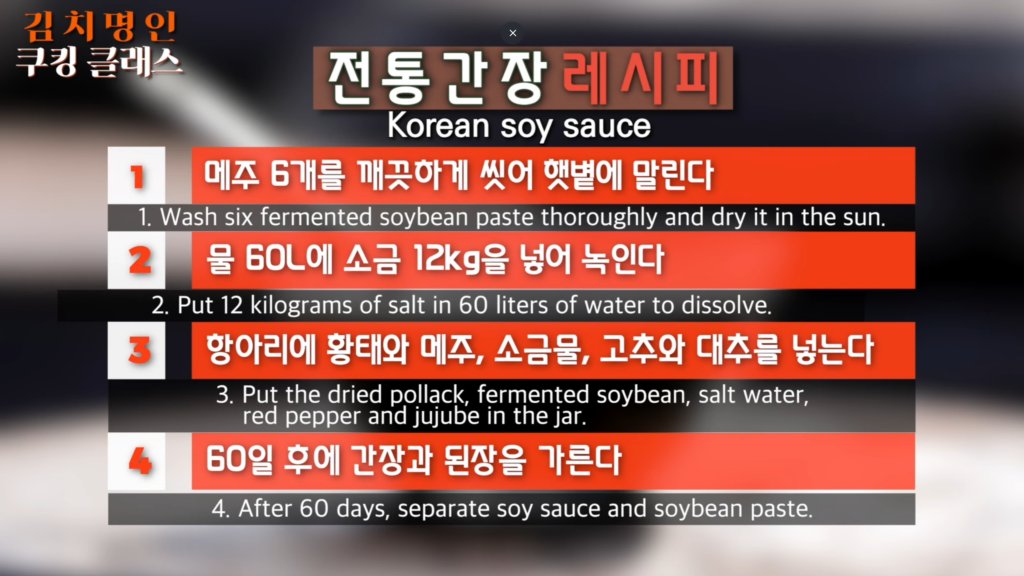

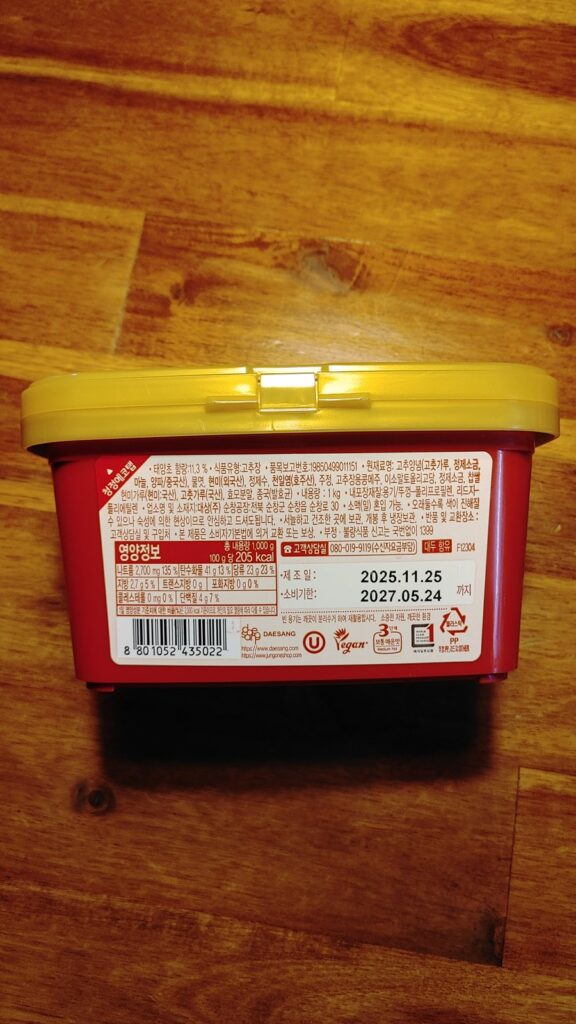

Back in the 1990s when my mother used to cook, doenjang-guk (soybean paste soup) was very common. There was much less food available than now, and fewer imported agricultural products as well. At that time, lifestyle diseases and obesity were quite rare. Now, as a parent raising children myself, when I talk with my family about it, we realize that the foods our family ate back then had extremely few ultra-processed foods compared to now, and there were virtually no genetically modified foods. To create flavor in those days, most seasonings like doenjang (soybean paste), gochujang (chili paste), salt, and soy sauce were made at home, and there weren’t many chemical additives used to artificially enhance taste.

What is Jjigae (찌개)?

According to Korean dictionaries, jjigae is first defined as a side dish made with less broth (less water added compared to guk or tang), cooked with tofu or vegetables, gochujang (chili paste), or doenjang (soybean paste), seasoned and slightly salty. Of course, restaurants sell menu items like doenjang-jjigae (soybean paste stew) and gochujang-jjigae (chili paste stew). They’re generally served as part of a baekban (set meal). If you order doenjang-jjigae baekban, you get doenjang-jjigae, and if you order jeyuk-baekban, you get jeyuk (stir-fried seasoned pork) along with various side dishes.

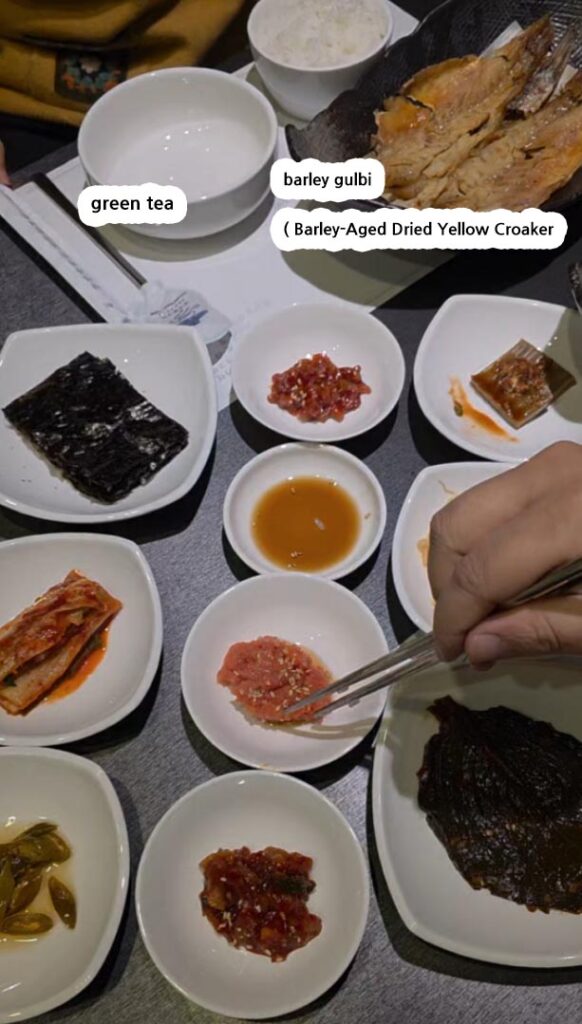

Jjigae generally has strong seasoning, making it perfect for mixing with rice or pairing with rice – they’re an ideal match. It’s commonly eaten together with rice, and the most popular jjigae menu items include kimchi-jjigae (kimchi stew), doenjang-jjigae (soybean paste stew), dubu-jjigae (tofu stew), jogi-jjigae (yellow croaker stew, mainly eaten by coastal residents), sundubu-jjigae (soft tofu stew), and haemul-doenjang-jjigae (seafood soybean paste stew) – the varieties are diverse.

When I have time someday, I plan to visit and introduce a jjigae restaurant located near Hongdae Station.

Fourth Category: Jeongol (전골)

If we compare jeongol to foreign examples, it’s similar to shabu-shabu. In China’s case, it’s also similar to malatang. The cooking method involves each home or restaurant preparing their own broth separately, then during cooking, adding various vegetables and meat to the broth and boiling it. When jeongol is served during a meal, it’s positioned in the center of the dining table. Multiple people sit around it and use ladles to scoop small portions onto their individual plates.

When I was young, jeongol didn’t exist, but nowadays people eat jeongol frequently. The main season for eating it is during winter when you crave warm broth.

The names of jeongol dishes are diverse. They vary greatly depending on the ingredients used: haemul jeongol (seafood hot pot), gopchang jeongol (intestine hot pot), beoseot jeongol (mushroom hot pot), bulgogi jeongol (marinated beef hot pot), mandu jeongol (dumpling hot pot), shabu-shabu, and so on. For example, in the case of gopchang jeongol, since the main ingredient is gopchang (intestines), it’s named gopchang jeongol.

When Visiting Restaurants in Korea…

Generally, guk is provided as a basic side dish with every meal. And of course, refills are available. The type of guk varies depending on what food each restaurant serves. In Korean restaurants that serve spicy food, in a way, kongnamul-guk (bean sprout soup) or miyeok-guk (seaweed soup) may be served to soothe the spicy taste.

If you’re eating samgyeopsal (pork belly) or galbi (ribs), doenjang-guk (soybean paste soup) or kongnamul-guk (bean sprout soup) may be served accordingly. In winter, most soups provided by restaurants are served warm.

What Are the Key Differences?

The first difference is cooking time. Jjigae and guk have shorter cooking times compared to tang. For example, gomtang or galbi-tang are cooked over low heat for a minimum of 1 hour to as much as 12 hours to tenderize the meat. This is to extract the broth from inside the rib bones.

If you visit Korea, you should definitely try galbi-tang or gomtang. They’re available near Hongdae too, and the price is around $10. If you want to try something more unique at that time, I recommend trying suyuk. Suyuk is meat that has been boiled for a long time until tender, then sliced thin and served.

Sugar Free Options?

Guk dishes that don’t contain sugar or syrup include bugeo-guk (dried pollack soup), kongnamul-guk (bean sprout soup), doenjang-guk (soybean paste soup), mu-guk (radish soup), siraegi-guk (dried radish greens soup), baechu-guk (napa cabbage soup), and miyeok-guk (seaweed soup). This is because Korean cooking methods for these dishes don’t use sugar (just as my mother did). An interesting fact is that these soups are also GMO-free.

My wife adds about a teaspoon of sugar to kimchi-guk, but if I were to make kimchi-guk, I wouldn’t add sugar. I don’t like that slightly sticky, clinging feeling on the tongue that comes from foods with sugar.

And most tang dishes don’t use sugar either. I was born in Andong, Korea, and people in Andong don’t particularly like sweet foods. Even now, when preparing meals for my children, I absolutely don’t use sugar when cooking. (I wonder if my children understand their father’s heart – that since they’ll eat ice cream and snacks outside anyway, they should eat a little less of it at home?)

Tang dishes that don’t contain sugar include gomtang, galbi-tang, and so-galbi-tang. You can tell as soon as you taste them. And in traditional Korean cooking methods passed down through generations, these tang dishes don’t use sugar.

Haemul jeongol (seafood hot pot), gopchang jeongol (intestine hot pot), beoseot jeongol (mushroom hot pot), bulgogi jeongol (marinated beef hot pot), mandu jeongol (dumpling hot pot), and shabu-shabu contain small amounts of sugar because they need to be a bit sweet. However, I can’t really compare the taste between American maple syrup and sugar, but perhaps maple syrup, being sweetness extracted from trees, is a bit healthier? In Korea too, there’s an increasing trend of using organic sugar rather than white sugar. There’s a perception that unrefined sugar is healthier than refined sugar.

One Thing Korean Mothers Always Consider When Preparing Meals

My father and the elderly generation said they wouldn’t eat rice without guk. It’s convenient to eat, and back in the day, due to Korea’s ‘ppalli ppalli’ (hurry hurry) culture, people didn’t even talk during meal times – they just ate their rice. Guk is convenient to prepare, and once you get the hang of it, you can prepare guk within 30 minutes. That’s why even a simple guk is prepared for meal times.

Once guk is prepared, it’s not finished in one meal – if it’s eaten in the morning, enough is prepared to be eaten twice, including dinner. It reduces meal preparation time and also reduces ingredient costs, making it a food that embodies frugality.

Conclusion

Cooking time increases in this order: Guk > Jjigae > Jeongol > Tang

Seasoning intensity decreases in this order: Jjigae and Jeongol > Tang > Guk

At every meal, guk and tang are served in individual bowls, while jjigae and jeongol are placed in large pots in the center of the table, and people serve themselves from them. Guk and tang are not served this way – mothers prepare one bowl for each family member.

How About this Article – What is Tank / Is Korean food Healthy?

Q1: What’s the difference between guk and tang?

A: Tang is an honorific form of guk (soup). Tang requires longer cooking time and more expensive ingredients than guk. Guk has a 6:4 or 7:3 ratio of water to ingredients and can be prepared within 30 minutes. Tang, however, is simmered over low heat for 1-12 hours to extract deep, rich broth flavors from bones.

Q2: Which Korean soups don’t contain sugar?

A: Most traditional soups, such as dried pollack soup, bean sprout soup, soybean paste soup, radish soup, dried radish soup, and seaweed soup, don’t use sugar. Among soups, gomtang (beef bone soup), galbitang (short rib soup), and sogalbitang (beef rib soup) are made without sugar. These dishes are GMO-free and are representative examples of healthy Korean cuisine.